Friday, August 26, 2016

Warning: this is long form writing, and a bit academic. Proceed at your own risk!

In this film, you will see a woman handkerchief tied to a man’s wrist, a pig’s head well shaved, teenagers more inventive than their elders so as to fight oppression…But you will not hear any dialogue. The words don’t prepare, accompany or comment the action in the film. It is not a silent film, but only a way to keep for cinematography certain moments in life where we do not speak. The spectator will perhaps have more freedom in his interpretation and we hope, a distinctive pleasure. Even if the menu we have prepared for you is made up of more raw than cooked.1

1 The synopsis of Alain Cavalier’s Libera me () at Cannes festival, 1993. http://www.festival-cannes.fr/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/2568/year/1993.html.

There are films that talk a lot; and there are films talk a little. But finally, there are films that don’t talk at all. Is talking essential to cinema?

Ingmar Bergman told us that he once by chance came across a print of Andre Rublev and watched it with utmost fascination, although he didn't understand Russian and the copy they watched has no subtitle. Apparently, although Tarkovsky and his collaborator may have spent considerable effort elaborating the film’s dialogue, Bergman and his friends were able to appreciate the film without it. Tarkovsky himself always maintained that the meaning of a scene is never to be found, or based on, the dialogue. In an ideal situation, words themselves should become “noises”, thus part of the non-distinguishable reality of the world.

This anecdote could be (or may have been) used to stress the fact that Tarkovsky is such a visual filmmaker, and that what ultimately matters in a film is how it looks. This is not the place to debate how much there is in this claim. But as I have always stressed, voice is not dialogue: Bergman may well ignore the meaning of what Rublev says, but he cannot ignore the way he says them.

At this point I believe it is à propos to quote Marcel Pagnol’s riposte to anyone who claims that sound is a dispensible property, that talking film is just canned theater. To this Pagnol replies, “Any talking film which can be shown silent and remain comprehensible is a very bad talking.”1

1 See “The Talking Film,” in Rediscovering French Film, ed. Mary Lea Bardy [New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1983], 91)

Pagnol’s logic, of course, doesn’t tell us what makes a good talkie. And it doesn’t even explain why some talkies of the end of 1920s are denounced as bad (for they surely cannot be shown silent and remain comprehensible). Imagine the following statistical study — quantifying the talkativeness in the history of cinema: for silent film, measure the amount of time taken by showing intertitles, as well as shots showing people talking enthusiastically (the amount of telephone scene!); and for sound films, the total time when human speech is heard. Naturally, we will see a whole spectrum of possibilities ranging from complete muteness (Murnau’s exemplary Der Letzt Mann), a generally speaking laconic use of dialogue (Akerman’s Jeanne Dielmann leaves speech out for most of the film’s three hours), to the average talkative (majority of films fall into this range), and finally the extremely talkative ones (from Victor Sjöström’s intertitle packed melodramas to His Girl Friday). Variances are attributable to national cinemas, filmmakers, and individual film projects. But if the sample is large enough and reasonably representative of the filmmaking practice (by representative I mean it should not consists of strictly canon or films of high artistic value, but instead, a random sampling of films made in the specific time and region, as Bordwell et al. suggest in their study of Classical Hollywood Cinema.), these variances can be evened out to reveal larger trends, for instance, trends of the decade, which might be helpful to answer the following questions: does the decade immediately follows the sound conversion show a rather high percentage of talking and does this percentage drop in the following decades? Exactly how talkative is 1940s compared to 1930s? And contemporary cinema? Is there a difference between national cinemas, say, between French and American?

Maybe talking is indeed dispensible. But what does that leave to sound cinema? Does it mean we can dispense sound all together? Or sound can do something beyond dialogue, beyond narrative comprehension?

Even before the kind of statistical study I mentioned is conducted (there is a thousand details to be taken care of), it is fairly safe to make the following predictions: first, silent films are more talkative than we remember. The lack of technological means to reproduce the sounds uttered does not deter the abuse of speech. Second, narrative integration marks a sharp increase of the need for intertitles. Third, throughout the history of cinema (since 1908 at least), the overwhelming majority of filmmakers have relied on talking as a critical narrative and expressive device. Commenting on Eisenstein’s motivation of rejecting talkie — because it leads to “highly cultured dramas” — Kracauer inadvertently confirms the above truth,

Eisenstein did not seem to realize that what he considered a consequence of dialogue actually existed long before its innovation. The silent screen was crammed with “highly cultured dramas”.

Not only the silent screen. And not only the genre of “highly cultured dramas” in a weirdly derogative sense. Both Hawks’s screwball comedy and Godard’s elite intellectualism feature one same star, that of people talking non-stop.

But there always exists in cinema an opposite to this incredulous amount of talking. Laconic films, or even mute films (the two terms are from Chion, FSA, 327), are not to be confused with silent (or more appropriately, deaf) cinema. The muteness of a film can be justified by the unusual protagonists who cannot speak (animals in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Bear(1988), or prehistorical humans in the same filmmaker’s Quest for Fire (1981)), does not want to speak (for Themroc (1973), Shindo Kaneto’s Naked Island (1960), as well as Cavalier’s Libera Me (1993), any speech would seem to jeopardize the silent determination that amounts to a savage violence), or alternatively, is engaged in some “unspeakable” affair (the fact that nobody speaks adds palpable psychological tension to The Thief (1952), where the protagonist is visibly tortured by his treason). If only narrative fiction feature with live human being is counted, then it turns out that there are not many films where nobody ever speaks a word. Apart from these examples, there are laconic films of a different nature: Le Bal (1983), Le Dernier Combat (1983). The complete muteness of these two are not justified similarly to the examples cited above, for their tone is rather light and comic.

While mute films are a rarity in film history, laconic films are not. There are plenty of films that explicitly reject talking as a convenient way of expressing thoughts. For a number of classical film theorists, this is the category that sets up against the talkie proper (or as Chion put it, the logorrheic, the extreme loquacity) — speech is allowed, in condition that it be used wisely and sparsely. Similarly, these films can be justified by their taciturn heroes (Clint Eastwood, Takeshi Kitano are the most obvious examples), whose lack of words may be compared to the lack of expression of Sessue Hayakawa, a quality touted by Balázs and his cohorts. Or the film’s aural sparsity conveys a directorial intension. For Jeanne Dielman, the large chunks of mute passages are contrasted with bursts of speech, which endows the letter reading scene with an otherworldly quality amidst a world of solitude, because it is the only lengthy speech act in more than three hours of silent performing. The Mill and the Cross (2011) is a recent case where speech is only used by three main characters (the painter, the banker, and Mary played by Charlotte Rampling). And the myriad of minor characters make ample use of various non-linguistic utterances — not that they refuse to speak; they don’t have a language to speak through. Indeed, this “contrasted tacitness” seems to become the prominent feature of a particular kind of art house cinema. To cite recent examples, both Turin Horse (2011) and Silent Light (2007) make use of long segments of silent performances of the daily chore to generate tension and a sense of heaviness (for Tarr) or sacredness (for Reygadas).

The amount of speech actually used by any given character, or by all characters in a film is in itself not important. What matters is the difference between our assumption of the amount of speech in a certain context and the actual amount presented by the film. We tend to assume, not necessarily consciously, not only about a character’s talkativeness, but also about how a certain narrative act would be resolved in speech. Watching a Bela Tarr film one has little expectation for loquacity (despite the fact that several of his films are indeed so) and therefore is seldom surprised by its long mute passages. For me at least, the combination of muteness and long, elaborate camera movement combine to form Tarr’s signature style.

This long introduction serves to bring three recent films into context. These films are made in very different circumstances, and for very different target audience. Yet there is one thing they share: a deliberate avoidance of human speech. How is the lack of speech justified in these films and what do the films do to compensate that lack? What do these films prove, or achieve, to sound cinema, in the absence of speech. These are the questions I want to explore.

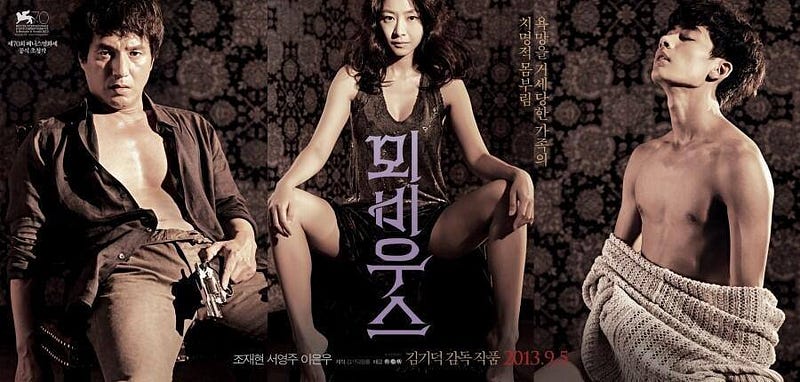

Moebius (2013)

It is a risky business to admit any love for Kim Ki-duk’s recent work, Moebius, which is no doubt a culmination of the often bizarre, certainly brutal and curiously provocative motifs found in nearly all his works. Compared to Kim David Cronenberg is just a bourgeois gentlemen with a little crazy fantasies.

A man is having an affair. A mother confronts him and attempts to castrate him. She fails. So she castrates her son in his stead. The father is devastated. He seeks help from the good old Google and discovers a curious way of achievement sexual orgasm through self-abrasion: rubbing stones on your skin so hard that it hurts terribly. Meanwhile, the Dad’s mistress (played by the same actress of course) hooks up with the son….

But the story is not the point here. Not even Kim’s mastery of the filmic medium and his undeniable talent in staging a scene. The point is that there is no dialogue. Nobody is mute in this film. Yet they all refuse to speak. Not a single word. They do make a lot of other sounds, though, like animals in pain. While Kim’s previous works are not exactly talkative and in some films (such as 3 Iron) main characters seldom speak already, this film seems to have announced a formal refusal of the human language. What would be the effect of this formal choice? How would the film feel with some dialogue? Brian Tallerico his review of the film says,

The decision to craft “Moebius” as a dialogue-free piece has a dual impact. First, it heightens viewer involvement as we have to lean forward, concentrate heavily on the blocking and staging to follow a story that has no subtitles or other traditional sign markers. Second, it creates an exaggerated world like a theatrical piece that chooses movement or interpretative dance, for example, to convey its themes instead of narrative. And that element adds to the black comedy aspect of “Moebius” — this is inherently ridiculous but it’s made more so by no one commenting in any way through dialogue on that ridiculousness.

Following along this line of thinking, it is perhaps productive to look at this film as a sort of avant-garde theater practice that relies heavily on symbolism and intellectual reflection. It is not that characters seek to communicate through means other than language. They simply do not wish to communicate, except through aggressive or erotic gestures. Nothing is mundane is this film. Every act is a matter of life and death. Yet it is a dance without elegance. The film happens to record it.

The Tribe (2014)

The Tribe has a good reason to not to use speech. It is set in a deaf school where nobody actually can speak. In a sense, they do talk. Only that they are using sign language. This is not completely new to cinema. Children of Lesser God (1986) also features a school for the deaf and a deaf actress (Marlee Matlin) in the leading role. There are numerous other films that contain snippets of sign language uses.

Sign language is just like any other language. For those who speak Ukranian sign language, this could be a very talkative film. Yet when people (including the filmmaker himself) refer to it as “silent”, they seem to imply that in silent films there is no talking. In an interview with Dazed Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy said the following:

Since my first year of film school, I’d had the idea to shoot in the way silent movies were made. Throughout history, plenty of movies have paid homage to silent movie, but only in terms of style. The way I’ve done it is to use the spirit of silent movies: it’s absolutely detached with no borders, just as it used to be when cinema was beginning and searching for its way.

I see it is a huge error to confound films with no audible dialogue with silent cinema. In silent films, people talk a lot. But there is a sound proof glass wall in front of us audience so we can’t hear anything. Yet the characters or players understand each other not because they wave their hands and move their bodies desperately (quite often they do), but because they actually can hear each other. Their communication channel is verbal (Chaplin’s case is slightly different as he does perform pantomime instead of talking). We know the sound is there; but just can’t hear it. In a sign language film this is decidedly not the case: we hear exactly what the characters hear. And there is no physical barrier between us.

As for the fact that in both cases people use gestural language to communicate, the similarity is only superficial. In silent films the body language remains rudimentary, that is, universal. It conveys things that all human (or even apes) would understand. On the other hand, I don’t know anyone who can understand the Ukranian sign language. For the international audience (even the director himself, who needs an interpreter) this film presents a linguistic opacity impossible to penetrate. But the script is there; it is verbal, and somebody wrote it in advance.

Now, compare this to the experience of watching a foreign film that has no subtitle, there is also something different. Although we can’t understand the foreign language in question, we can gather a lot from the vocal performance. Indeed, we are cognitive trained since infancy to derive so much emotional content from tonal qualities, accents, intonations, that we are able to detect the true intention beyond what is is actually said.

I am not sure if such subtleties and nuances of expression can exist in sign language; even if it does, I am not trained to recognize them. There is a good chance I might misrecognize things precisely because sign language shares a same communicative vehicle of the abovementioned univseral body language of all human beings. A sudden movement of hand in front of people’s face may signify a violent, aggressive intention here, but just a banal yet quick response there. This is perhaps why the filmmaker sometimes made the actors “say” things differently because he didn’t like the gesture. I figure this means that he is, like me, judging the performance from the universal body language perspective.

All is Lost (2013)

Enough of international art house. Now for something completely different: a Hollywood film featuring a familiar face. All is Lost is a daring experiment in the Hollywood context and it would certainly not materilize were it for Robert Redford’s monumental effort. After all, he has a huge stake in this film as he has to do all the acting!

My main point regarding this film is this: a film such as this would not be possible in the silent era.

Why not? Isn’t it true that nobody talks any way? Wouldn’t this be an ideal silent film, which actually doesn’t have the technical means to record talking?

If you agree that such a film cannot be made in the silent era, you are agreeing on one thing that I have reserved for this moment. Sound cinema is not all about voice. It is even less about music, which was almost always there. Sound cinema reinvents noises. It changes our perception of the filmic world and makes diegetic sounds a constitutive part to our experience. And this film is a good example to illustrate what the “banal” sound effects can do in a film.

It is true that the film is not completely mute. Redford emits often one syllable utterances: GOD, FUCK. And when he sees the ocean liner he can’t help but shouts (like everybody else), “hey help, I’m here, help! here!” It even contains some voice over in the very beginning. This is a decision that the filmmaker made. In the eyes of a purist it might be a compromise, a moment of weakness. But all these is no big deal. The majority of the film still holds up exclusively with largely realistic sound effects: flapping of water, cracking noise (can’t stop thinking of celery when I hear these) of the boat, thunderstorm and other nature sounds, the sounds that his body makes, grumbles, panting, sobbing, wheezing.

Is there music? At quieter moments I heard distant brass tune that sounds like foghorns. But the effect is subtle. Underwater shots of fishes are sometimes accompanied by ocean music. There are also moments of thunderstorm when I hear the music starts to play explicitly, albeit still in background. The foreground sound of this film is always the sfx.

There is a well known anecdote regarding this matter. Hitchcock made a film with similar setting: Lifeboat (1943). And he is reported to refuse to use music, then a convention at the studio. He says, “ask the composer where did the orchestra come from in the middle of ocean and I will use music.” To this the composer (Hugo Friedhofer) replied, “ask Mr. Hitchcock where the camera came from and I will tell him.”

Now that I think of it, the film can indeed be made in the silent era — with continuous musical accompaniement. It will be just another Flaherty thing: man against nature, and man survives. But the film world formed this way is very different from the film world formed through diegetic sound effects. The formation of audiovisual diegesis is a crucial step in the evolution of the language of cinema, a step that is currently massively misrecognized and undertheorized.

This article is not properly terminated here. Yet as a blog post it is already terribly overlength. To be continued.