A Note on Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Wednesday, May 07, 2008

Michelangelo once explained to a Portuguese artist Francesca da Hollanda, in a contemptuous tone, why Flemish landscape is not a medium of artistic expression as good as his human bodies:

They paint in Flanders only to deceive the external eye, things that gladden you and of which you cannot speak ill. Their painting is of stuffs, bricks and mortar, the grass of the fields, the shadow of trees, the bridges and rivers, which they call landscapes, and little figures here and there. And all this, though it may appear good to some eyes, is in truth done without reason, without symmetry or proportion, without care in selecting or rejecting.’ And he concluded that these ‘landscapes’, like the panoramas of Patinir, are only suitable for ‘young women, monks and nuns, or certain noble persons who have no ear for true harmony. (qtd. In Clark 26)

Michelangelo was probably right in the sense that he failed to see the platonic ‘artistic ideal’ being represented in those paintings. Because of his tremendous influence, together with the gigantic achievements of Italian High Renaissance, the northern art, which until 16th century had enjoyed much popularity, was degenerated by terms since as ‘primitive’ and ‘backward’.

Today this distorted evaluation which lasted almost for three centuries seems no longer perceivable. In art history textbooks there is always this special chapter reserved for ‘northern renaissance’ masters: Jan Van Eyck, Roger van der Weyden, Joachim Patinir, Pieter Bruegel and a half dozen others. A man of vision once wrote, not without irony, ‘At the present moment, it is true, we have achieved an unprecedentedly tolerant eclecticism. We are able, if we are up-to-date, to enjoy everything, from Negro sculpture to Luca della Robbia and from Magnasco to Byzantine mosaics.’ (Huxley 10)

It might seem to some undiscriminating eyes that Flemish artists are all proudly contributing to their own splendid era. This is of course only a misunderstanding. As we know, it is the Italianism which were constantly in demand by Spanish commissioners and many northern painters enjoying high fame at the time were busy producing them. It was impossible for Bruegel to not to notice these influences and some scholars made observations that he indeed learnt from Italian mannerism and, instead of creating superficial imitations, had assimilated those elements into his own artistic expressions after his visit to the south. But this is not always the case. Take the example of Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1565), the contrapposto of the woman is definitely an Italian one which reminds us of Botticelli’s Venus. Instead of seeking protection under Jesus’ feet out of fear, she proudly stands amongst the Apostles and the Pharisees, looking down on Jesus with such an indifferent smile as if she was a goddess being sent down to reconcile a human discord. The explicit mannerism not only stands out of the overall harmony of the work but also imposes an unnecessary sacrifice of realism for a twisted feminine beauty. Another less obvious example is the holy women group in The Calvary, as I will mention later. It appears to me, then, while regarding Peter without any hesitation as an peasant like the others, the artist still had some reserved respect for ‘our lady’ and insisted on depicting her in the Italian way.

Nevertheless Bruegel’s work evokes feelings that are totally different from those of Italian high renaissance. The Italian masterpieces exude an ideal form that does not exist except in artists’ perception. Bruegel, on the other hand, imparts to us a perfectly visible and intimate range of phenomena. We need not to be purified by, or surrender to its superiority. The Flemings and their ways of living amuse us and remind us, with utmost sobriety, what we really are.

In this sense, Bruegel’s view of the world have some similarities with that of an Asian artist. In fact, it could be said that he is as far away from the tradition of Bacchus-Dionysus-Apollo as a Chinese painter is. He never painted a nude or a portrait, like a Chinese painter. Chinese do have nude pictures. But they are pornography, not body art. Some of the figures of early Bruegel are nude too, like those in Allegory of Pride (1557), but they are not body art either. It is obvious that both Bruegel and Chinese painters had given up human body as an ideal representation of virtue or beauty. And it is not difficult to notice that the Chinese way of depicting figures in a landscape resembles Bruegel’s considerably—they are all paper-thin silhouettes moving awkwardly in their cumbersome outfits. The landscape itself, especially the rocks, bear striking resemblance to their Chinese counterpart. As Huxley puts it, ‘they are intensely poetical, yet sober and not excessively picturesque or romantic.’ (Huxley 19) Conversely, the landscape tradition of western art which, according to Kenneth Clark, dates back to Giorgione and Titian, perfected in the hands of Poussin, Lorraine and their northern counterpart Constable, Gainsborough, means nothing but ‘pastoral’, ‘Acadian’, a Greek ideal of soothing, retreated harmony. Those half naked semi-deities stretch themselves here and there with typical stately Mediterranean poses, which is a major theme of western landscape up to 20th century, have nothing in common with Bruegel’s pot-bellied, downright grotesque figures. Thus it is understandable that, failed to see anything poetic there, Clark didn't have any choice but to put Bruegel into a category of “the landscape of fantasy.” (Clark 27)

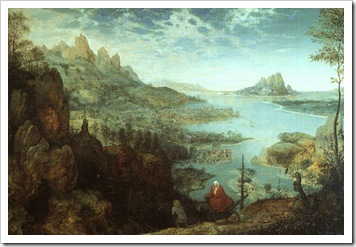

How did Bruegel come to conceive the landscape in this way then? Although Joachim Patinir is the first recognized landscape painter in the sense that he turned landscapes into an independent subject of the painting, his landscapes are still tinted with religionary or mythical figures situated in the centre of composition. In various versions of St. Jerome the rocks are almost as good as ideal rocks, but they are still one step from being called poetic (with the notable exception of Landscape with Charon’s Boat, 1616). The landscape series of Bruegel, on the other hand, were completely human scenes. It is less imaginary than religious paintings (who ever saw St. Jerome sitting in the midst of a desert or Mary resting in her flight to Egypt?) but still higher than our daily perception of the world. This series of paintings, commissioned in 1565 by his friend Jonghelinck, is first of all a direct inheritance of a Flemish tradition of decorating calendars in prayer books with miniature scene of outdoor work and play, as seen in The Money Changer and His Wife (1514) by Quentin Messys. I am glad to note here that this is also a tradition practised in China. Although Catholic saints and Greek deities are almost extraterrestrial beings to our happy Chinese ancestors, they managed to fill the pages with ancient aphorisms and useful agriculture knowledge, which proved to be as enjoyable as a Book of Hours. However, Bruegel surpassed successfully any calendar art ever existed before by bequeathing the theme with timeless art forms and full-fledged poetic imagination.

How did Bruegel come to conceive the landscape in this way then? Although Joachim Patinir is the first recognized landscape painter in the sense that he turned landscapes into an independent subject of the painting, his landscapes are still tinted with religionary or mythical figures situated in the centre of composition. In various versions of St. Jerome the rocks are almost as good as ideal rocks, but they are still one step from being called poetic (with the notable exception of Landscape with Charon’s Boat, 1616). The landscape series of Bruegel, on the other hand, were completely human scenes. It is less imaginary than religious paintings (who ever saw St. Jerome sitting in the midst of a desert or Mary resting in her flight to Egypt?) but still higher than our daily perception of the world. This series of paintings, commissioned in 1565 by his friend Jonghelinck, is first of all a direct inheritance of a Flemish tradition of decorating calendars in prayer books with miniature scene of outdoor work and play, as seen in The Money Changer and His Wife (1514) by Quentin Messys. I am glad to note here that this is also a tradition practised in China. Although Catholic saints and Greek deities are almost extraterrestrial beings to our happy Chinese ancestors, they managed to fill the pages with ancient aphorisms and useful agriculture knowledge, which proved to be as enjoyable as a Book of Hours. However, Bruegel surpassed successfully any calendar art ever existed before by bequeathing the theme with timeless art forms and full-fledged poetic imagination.

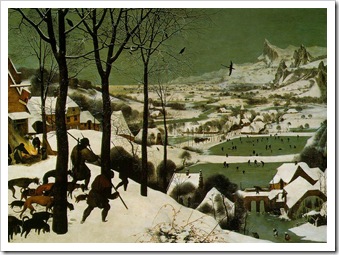

In Tarkovsky’ s film The Mirror, in which the director tried to reconstruct his personal yet universal memory of childhood during World War II, there is such a scene of shooting range which could be definitely called Bruegelian in that it gave us the same kind of frustrated nostalgia in front of Hunters in the Snow (1565). The same with The Return of the Herd (1565), The Harvesters (1565), The Haymaking (1565) and Gloomy Day (1565), everyone of which showed not only a perfectly balanced landscape, but also an emotion connected to the scene, which are readily aroused in audience of different cultural backgrounds. Some other paintings of Bruegel, such as The Fall of Icarus (1555-8), Conversion of Saul (1567), Parable of the Sower (1557), Magpie on the Gallows (1568), although dealing with mythical, religious and proverbial subjects respectively, also incorporate a superb rendering of landscapes.

In Tarkovsky’ s film The Mirror, in which the director tried to reconstruct his personal yet universal memory of childhood during World War II, there is such a scene of shooting range which could be definitely called Bruegelian in that it gave us the same kind of frustrated nostalgia in front of Hunters in the Snow (1565). The same with The Return of the Herd (1565), The Harvesters (1565), The Haymaking (1565) and Gloomy Day (1565), everyone of which showed not only a perfectly balanced landscape, but also an emotion connected to the scene, which are readily aroused in audience of different cultural backgrounds. Some other paintings of Bruegel, such as The Fall of Icarus (1555-8), Conversion of Saul (1567), Parable of the Sower (1557), Magpie on the Gallows (1568), although dealing with mythical, religious and proverbial subjects respectively, also incorporate a superb rendering of landscapes.

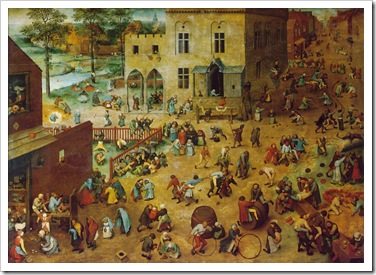

One category of Bruegel’s painting is the so-called anthropological studies of folk life. These include the famous Peasant Dance (or Kermis, 1567-8), Peasant Wedding (1567-8), Children’s Game (1560), The Battle between Carnival and Lent (1559) and The Blue Cloark (or Netherlandish Proverbs 1559). These paintings shocked us with an unprecedented realism and earned him the name of ‘Peasant Bruegel’. Jean Videpoche describes,

One category of Bruegel’s painting is the so-called anthropological studies of folk life. These include the famous Peasant Dance (or Kermis, 1567-8), Peasant Wedding (1567-8), Children’s Game (1560), The Battle between Carnival and Lent (1559) and The Blue Cloark (or Netherlandish Proverbs 1559). These paintings shocked us with an unprecedented realism and earned him the name of ‘Peasant Bruegel’. Jean Videpoche describes,

Frozen into grimaces by the cold, seared with squint lines by the summer sun, they make painful contrast with the festival backgrounds which they find themselves…force their work-shackled muscles to caper in unaccustomed dances. But their faces never lose the dull, brutal cast that their work has set upon them. (Huxley 51)

The rollicking figures incite less moral lessons or religious feelings compared to the others, but they nevertheless initiated a great tradition started by Bruegel and carried on by Millet, Van Gogh.

Another category of his works is maybe best titled as ‘being an observer of this miserable world that is ours’. By incorporating his fellow country men into Biblical events, Bruegel creatively decoded the significance of those events in his contemporary world. This includes The Tower Babel (1563), Census at Bethlehem (1566), Massacre of the Innocents (1566). There are a few others, though not of biblical content, served the same purpose here. This includes: The Blind leading blind (1568), The Cripples (1568). The best of them, The Carrying of the Cross (sometimes called Calvary, 1564) turned Golgotha into a typical Flemish village. We are shifted from the role of passionate Christians to unsuspected peasants who are ready to enjoy just another free show of public execution. The suffering of Jesus, together with the significance of it, is no longer the main subject of the composition. The people, our people, becomes something that unexpectedly attracts our attention. Perhaps the similarity of persecution and fest is more significant than the death of Jesus Christ? It is worth noting that in the Carrying of the Cross (c. 1505) by Hieronymus Bosch, the man Bruegel was indebted to in his ‘comedy & proverb’ phase, Jesus was shown with a sleeping tranquility amongst various terrifying devil-like faces. Although it is an ‘unflinching exposure of the bestiality of man toward man … the insane lust for violence characteristic of a vindictive mob in his day or our own,’ (Foote 58) those extravagant faces externalize this eccentric pleasure of enjoying human disfigurements. Another Bosch’s painting, The Crowning with Thorns (1508), bears less devilish faces but still vicious eyes. The Bruegelian crowd, on the other hand, are consisting of just ordinary people with a jolly indifference. Such are the different levels of artistic expression.

Another category of his works is maybe best titled as ‘being an observer of this miserable world that is ours’. By incorporating his fellow country men into Biblical events, Bruegel creatively decoded the significance of those events in his contemporary world. This includes The Tower Babel (1563), Census at Bethlehem (1566), Massacre of the Innocents (1566). There are a few others, though not of biblical content, served the same purpose here. This includes: The Blind leading blind (1568), The Cripples (1568). The best of them, The Carrying of the Cross (sometimes called Calvary, 1564) turned Golgotha into a typical Flemish village. We are shifted from the role of passionate Christians to unsuspected peasants who are ready to enjoy just another free show of public execution. The suffering of Jesus, together with the significance of it, is no longer the main subject of the composition. The people, our people, becomes something that unexpectedly attracts our attention. Perhaps the similarity of persecution and fest is more significant than the death of Jesus Christ? It is worth noting that in the Carrying of the Cross (c. 1505) by Hieronymus Bosch, the man Bruegel was indebted to in his ‘comedy & proverb’ phase, Jesus was shown with a sleeping tranquility amongst various terrifying devil-like faces. Although it is an ‘unflinching exposure of the bestiality of man toward man … the insane lust for violence characteristic of a vindictive mob in his day or our own,’ (Foote 58) those extravagant faces externalize this eccentric pleasure of enjoying human disfigurements. Another Bosch’s painting, The Crowning with Thorns (1508), bears less devilish faces but still vicious eyes. The Bruegelian crowd, on the other hand, are consisting of just ordinary people with a jolly indifference. Such are the different levels of artistic expression.

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understand

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the

torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

Musée des Beaux Arts

W.H. AUDEN

Works cited

Barnouw, Adriaan J. The fantasy of Pieter Brueghel New York: Lear, 1947.

Clark, Kenneth. Landscape into Art. New York : Charles Scribner’s sons, 1950.

Delevoy, Robert L. Bruegel : historical and critical study. Geneva : Skira, 1959.

Foote, Timothy. The world of Bruegel. New York : Time-life Books, 1968.

Gibson, Walter S. Bruegel. London : Thames and Houdson, 1977.

Grossmann, F. Bruegel: the paintings, complete edition. London, Phaidon P., 1966.

Hollanda, Francisco de. Dialoghi romani con Michelangelo. Milano : Rizzoli Editore, 1964.

Huxley, Aldous. The elder Peter Bruegel. New York : Willey Book Co., 1938.

Koch, Robert A. Joachim Patinir. Princeton : Princeton UP, 1968.

Mander, Carel van. Dutch and Flemish painters. New York : Arno Press, 1969.

Snow, Edward. Inside Bruegel: the play of images in Children’s games. New York : North Point, 1997.

edit

1 comment:

Stumbled upon this blog post, curiosity piqued.

Thought it excellent and was moved to comment. Not an expert, but your post is educational to people like me. Came here by way of search trying to research the depiction of the pastoral in Flemish art (and beyond).

Post a Comment